An Introduction to Asset Allocation

Author: Marco Santanche

Apart from the specific strategies we are targeting, a very important factor contributing to your investment performance is asset allocation.

As simple as it might sound, asset allocation refers to the portion of our portfolio (capital) that we allocate to each investment. We can also break down the asset-allocation process in multiple steps, by allocating, for instance, a portion of our portfolio to equities, fixed income, and other asset classes. And following this first step, we allocate internally to each asset class according to our preferences.

Asset allocation is a very wide topic, so we will just introduce it in this episode, and we are going to analyze the different techniques going forward.

Do I need asset allocation?

The process of allocating capital dates back at least to Shakespeare’s time:

My ventures are not in one bottom trusted,

Nor to one place; nor is my whole estate

Upon the fortunate of this present year;

Therefore my merchandise makes me not sad.

W. Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice, Act I, Scene I

Whether we like it or not, asset allocation is unavoidable: even buying a single fund would result in allocating capital, which would just be 100% invested into it.

The problem is, allocating capital efficiently is very difficult and it should be dynamic. This is made easier by large portfolios, where 5% might mean a very large investment; for smaller portfolios, fees often eat out many of the benefits of allocating capital according to some rules, including potential returns.

Asset allocation is often paired with the concept of diversification; while both are unavoidable processes in the investment journey (again, 100% in a fund means some exposure to some risk factors, willing or not), they are not synonyms. With the former, we intend to expose our portfolio to specific risk and return factors, while with the latter, we are only discussing the benefits of reducing specific risk (often called idiosyncratic risk) by allocating capital in multiple assets. Even if our portfolio is built according to some specific asset-allocation rule, diversification benefits might be close to zero; that is, we could be exposed to the very same risks as the assets individually.

Naive portfolio management

To build an optimal portfolio has always been the desired outcome of many studies, both in academics and in practice. Indices, which started back in 1884 (Footnote 1), also consist of asset-allocation models by themselves, although they are not actual investments or companies.

In this context, we can introduce a few systems that have been considered basic or naive asset-allocation techniques:

- Price weighting. Some indices, such as the Dow Jones Industrial Average Index, allocate their capital according to the current price of the stocks that are included in their portfolio. This will result in allocating higher amounts of capital to higher prices of the stocks.

- Market cap weighting. The most famous market cap weighted index is definitely the S&P 500, an equity index that assigns a higher weight to companies which have a higher market capitalization.

- Equal weighting (1/n). As the name states, this system allocates equal portions of our capital to each individual constituent in the portfolio, resulting in a 1/n weight for each element (where n is the number of assets).

Although naive, all these systems have a reason to exist. Price weighting was born when stock prices were a new topic in money management, and prices probably reflected at least partially the value of a company (many legislations, for instance, require for a business to be incorporated and issue a minimum number of stocks). Moreover, the data was probably lacking at the time, and retrieving the market capitalization for each company might have been much more complicated than it is today.

The problem with price weighting is that, as it stands, the meaning of stock prices is dramatically reduced: it does not matter if a company’s stock price is 10 or 20, because the number of shares varies, and the actual value of the company (intended as market capitalization) could be the same.

This is exactly the reason why market cap weighting arose: market capitalization is the term used to identify the value available to investors at a specific point in time, or, as a proxy, it might reflect the value of the company as a whole.

The advantages of this approach are multiple: firstly, market capitalization can be compared, contrarily, to prices. Having 1 million shares or 2 million shares outstanding might impact the valuation of a company if we just look at its price, but if we look at market capitalization, we consider the total capital available - that is, stock price times the number of outstanding shares. In addition to that, a company with a high market capitalization is likely to be a very important company in the country or business area of interest, more established and, thus, a sort of proxy of the universe itself, or a very important factor that is both impacted by market changes or impacts the market itself with its own revenue, news, sales and more.

But while it makes sense to build a proxy of any market, it still exposes investors to some undesired behavior: first of all, many of the small weights in such indices can almost be completely removed, since the major holdings normally determine the moves in the market of reference. And this is also caused by a second reason: the high correlation (especially between those lower-capitalized companies and the major ones) of the stocks in the basket. An asset that constitutes a big chunk of the market will also be considered a risk factor for smaller companies, as it brings some systemic risk for the universe with itself.

Finally, equal weighting is more investor oriented, as it depends on the number of securities invested at some point in time. When market data lacks, and market capitalization is not available, being equally weighted is interpreted by many investors as a way to equally expose their own portfolio to the available options, avoiding preferring one asset over another.

While convenient, it is definitely not as neutral as it might seem: allocating large capital to smaller companies might expose to riskier factors than when the allocation is proportional to the importance (in terms of market capitalization) that those assets have in the market.

Every asset-allocation approach exposes our portfolio to multiple risks, that is understood. But while many tend to prefer one of these approaches, in particular equal weighting or market capitalization, it is also important to understand exactly what the rationale behind it is, and what disadvantages it brings.

Finally, a very important feature missing from all these systems is any predictive or future-oriented element, and the lack of proper risk management.

Modern portfolio theory

With the advent of computers and a more data-oriented approach to investments, a growing interest was piqued by a number of meaningful research papers in academia. While the target of this paper is not academic, it is important to know about some of them, such as Harry Markowitz’s famous paper (Footnote 2) from 1952, which led to the development of Modern Portfolio Theory.

In this masterpiece, a portfolio is built not only on the basis of some sort of neutrality, such as being exposed to all assets equally, or being exposed to the market as a whole; the target is to optimize the preferences of an investor, who might include in their views an expectation on either returns or risk.

In the very basic implementation, the expectations are nothing else than the average return over some specified horizon, while risk is assumed to be equivalent to the covariance matrix, which expresses the comovements of assets against each other (and the variance of each asset historically as well - that is, its “wiggling” around the mean). These elements are both obtained from the historical price series of each asset in the portfolio. It is because of this implementation that the optimization suggested by Markowitz is also referred to as Mean-Variance Optimization.

Analytically, this approach brought a major shift in the world of asset allocation: data is not only retrieved (like in market cap weighting), but also further processed to express expectations on the profitability and risk of each asset. The perspective is now much more interesting: for an investor, it does not only matter to keep in mind the importance of each asset (in the case of market cap or price weighting), or to avoid allocating too much capital in one asset rather than another one (equal weighting), but it also - and prevalently - matters to express, with their own portfolio, an expectation on future possible returns and their implied risks.

Is this sufficient? Probably not. Several criticisms have been moved in the years since the publication of this paper. However, the shift was sensible, and the benefits as well.

Practical considerations

The model suggested by Markowitz suffers from many pitfalls, as already mentioned. In particular, a real portfolio cannot follow entirely his academic work due to commissions and fees, the robustness of the model to small changes in its data, unreasonable portfolios (since the asset allocation suggested by Markowitz can be very concentrated), and more.

This is the reason why many companies invest differently. They still use - or at least, they should use - some model or approach to define targets and views, especially when allocating over single securities. For instance, they might apply a Mean-Variance Optimization only in a basket of securities that constitutes their portfolio - say, US equities.

However, most of them provide investors with a portfolio composition that is fixed with some prespecified assumption and based on investors' horizons and goals. For example, many provide the 60/40 portfolio (60% equities, 40% fixed income), or any other mix of assets, based on the assumption that the equity side adds risk and returns, while the fixed income side adds protection.

A follower of our series would already know that this does not necessarily hold true in recent times. But for simplicity, these simple allocation approaches remain the preferred ones by major banks and financial advisors.

When we move into asset management and hedge funds, the picture changes. These companies aim at more complex models, for several reasons:

- They normally manage large funds.

- They might have lower commissions and fees.

- They aim to provide investors with uncorrelated or superior (risk-adjusted) returns.

- They have a more dynamic style, dictated by their know-how, compared with individual investors.

In these cases, factor investing, trend-following strategies and more complex portfolio-optimization techniques help these companies in providing better results than buy-and-hold, fixed-proportion portfolios.

How do these companies invest? Normally, they aim at splitting their process into two steps:

- Strategic asset allocation: a process that aims for the long-term horizon, building a portfolio that reflects the expectations over a year or more.

- Tactical asset allocation: the more frequent version of the previous, which might adjust the weights of strategic allocation depending on short-term expectations in the markets.

Regardless of how the weights are determined (equal weights, Mean-Variance Optimization, or any other model), the two differ mainly in terms of the frequency and horizon for the views. Reviewing long-term expectations too often might result in giving in to the temptation of adjusting weights continuously, and possibly missing the initial objective. On the other hand, sticking to a specific portfolio for a long time might mean missing many short-term opportunities.

Market risk and the CAPM

In general, retail investors should focus on ETFs and pre-made diversified baskets of securities. The reason for this is one of the key findings in a model that dates back to the 1960s (Footnote 3).

An investor who does not possess the tools, skills or, even if they do, has no particular view on the future of the markets should invest in the market portfolio. This theoretical element consists of the representation of the entire market (although we can of course narrow down to sectors or industries, with similar conclusions), being a market cap weighted index of all the available securities. Since diversification, including Mean-Variance Optimization, reduces the idiosyncratic risk of each asset, the only source of risk that remains relevant to our portfolio is market risk, a.k.a. the risk that the entire market moves all together.

When we discuss recessions and protection using, for instance, fixed income instruments or low volatility factor, we are aiming at something that has a low or negative beta. It is the factor that “links” the returns of an asset or portfolio to the entire market returns. Some assets might overreact, some underreact, and some even react in the opposite way, adding protection to your portfolio whenever a negative return in the market happens.

And while the volatility of each stock can be diversified by approaches such as the Mean-Variance Optimization, that is not the case for beta. The portfolio will always have some exposure to market risk, no matter how well diversified it is; this is the main finding in the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) - which, by the way, relies on some very specific assumptions. No asset can reduce systemic (market) risk, apart from the so-called risk-free investment (which is often assumed to be the US Treasuries, although, especially in recent years, the risk in this type of investment is definitely growing).

If we cannot diversify well enough, why should we bother? For the CAPM, the best investment, especially in the absence of views or expectations, is a mix of the risk-free investment and the market portfolio. With a combination of the two, we can replicate all assets available, depending on our risk tolerance.

But in practice, the market portfolio is not observable, and it is also not possible to combine the market with any investment. That is one reason why ETFs and passive investing started: they try to replicate an industry, a subsector, or the whole market. In this way, the market becomes “investable” (although it is always an approximation) and we can build our CAPM-compliant portfolio. And this aligns to several recent articles and news headlines mentioning the underperformance of active investors, compared with passive funds: if it is too difficult to find an edge in the market, the passive investment is still the best baseline strategy.

Conclusions

Asset allocation is a broad topic. The naive and early portfolio-optimization techniques will help us in understanding the whys and hows of more recent models and ideas but, most importantly, to achieve our financial goals with awareness of the opportunities and risks involved.

What’s next?

In the next few episodes, we are going to determine the performance of asset-allocation models to a specific universe of ETFs that would make sense with the current environment and expectations. The aim is not to find a profitable allocation as of now (which might anyway be an outcome of our exercise), but rather to evaluate how consistent and different the various methodologies might be. We will also keep track of a few benchmark strategies, including equal weights and Mean-Variance Optimization.

Update on strategies

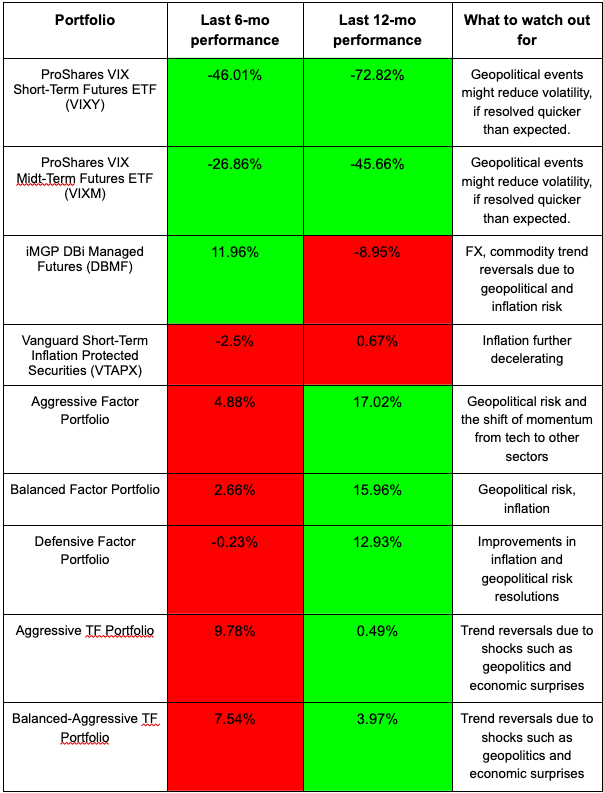

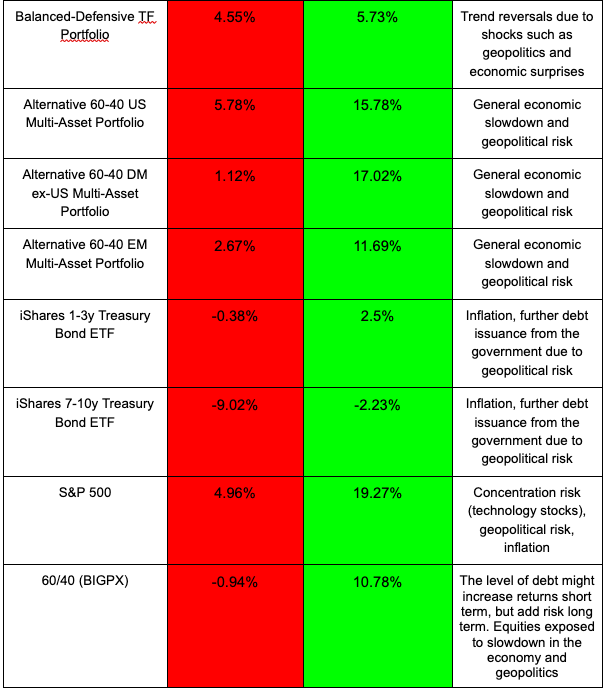

Apart from volatility, which spiked up compared to both six months and a year ago, and the VTAPX, all asset classes are mixed. In DBMF, we see an improvement over the past six months (more than +3% from last episode), but for all others, the performance is reducing, although the one year trend is positive.

Updates as of October 18 2023:

Footnotes:

(2) Harry Markowitz, Portfolio Selection, The Journal of Finance (1952)

(3) Capital asset pricing model

Trading strategy is based on the author's views and analysis as of the date of first publication. From time to time the author's views may change due to new information or evolving market conditions. Any major updates to the author's views will be published separately in the author's weekly commentary or a new deep dive.

This content is for educational purposes only and is NOT financial advice. Before acting on any information you must consult with your financial advisor.